Campo del Cielo refers to a group of iron meteorites and the area in Argentina where they were found. The site is located on the border of the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero, 1 000 kilometres northwest of Buenos Aires and approximately 500 kilometres southwest of Asunción (Paraguay). The crater field is 18.5 by 3 kilometres and contains at least 26 craters. The largest of these craters measures 115 x 91 metres.

It is estimated that the craters are 4-5 thousand years old. The first public mention of them dates back to 1576, but the indigenous people knew about them long ago. Thousands of fragments weighing approximately 100 tons have been found throughout the area, making this meteorite an absolute record breaker.

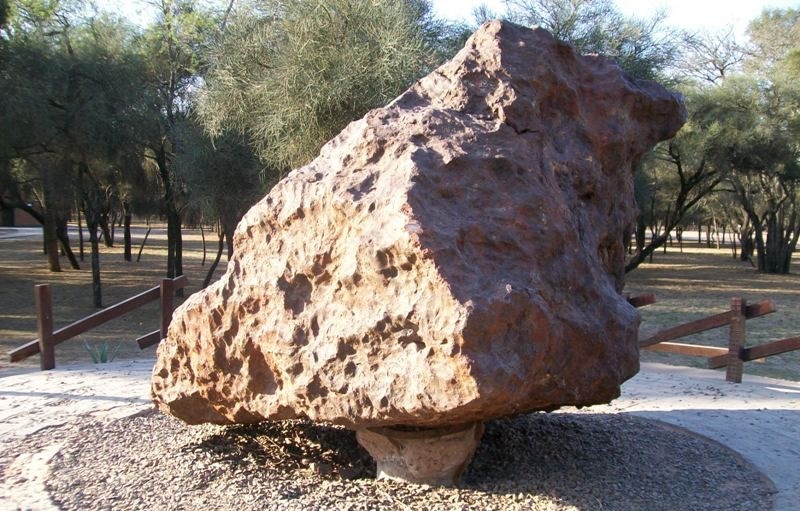

The two largest fragments, the 30.8-ton Gancedo and the 28.8-ton El Chaco, are among the heaviest single meteorite pieces found on Earth, after the Hoba meteorite (60 tons) and the Cape York meteorite (31 tons).

History

In 1576, the governor of a province in northern Argentina commissioned a military expedition to find the source of iron, which they had heard about from the stories of indigenous tribes who made weapons from it. Along with this story, they also learned of the strange origin of this iron, which they said "fell from the sky". Therefore, they also called the place Piguem Nonralta, which the Spanish translated as Campo del Cielo ("Field of Heaven" or "Field of Heaven"). The expedition soon succeeded and found a large metal boulder protruding from the ground. It collected several specimens, which were sent to the archives in Seville, but the find did not gain more attention at this point.

In 1774, Don Bartolomé Francisco de Maguna reportedly rediscovered these strange iron boulders and called them el Mesón de Fierro ("The Iron Table"). Maguna believed that they were the protrusion of an iron vein. Therefore, another expedition, led by Rubin de Celis, used explosives in 1783 to remove the soil around one of these meteorites to discover that it was not a continuous layer of material, but a solid rock. Celis estimated its mass at 15 tons and abandoned it as worthless. He believed it was formed by a volcanic eruption, not by the impact of a space body. Nevertheless, he sent samples to the Royal Society in London and published his report in a paper called "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society". These samples were later analysed and found to contain 90% iron and 10% nickel; thus definitively confirming an extraterrestrial origin.

Since the discovery of the crater field, thousands of pieces of iron weighing from a few grams to the aforementioned 30 tonnes have been found. The Otumpa, weighing approximately 1 tonne, was discovered in 1803. Part of this fragment, weighing 634 kilograms, was transported to Buenos Aires in 1813 and then donated to the British Museum.

In 1969, El Chaco (weighing 28 840 kilograms) was discovered 5 metres below the surface using a metal detector. It was recovered in 1980 and was a fairly well covered event in the media. But it wasn't just its discovery that deserved media attention. Meteorite collector Robert Haag, who attempted to steal the giant meteorite, was also in the spotlight. In 1990, he decided to take the meteorite away, only to be caught in the act by an Argentine highway patrolman. Robert Haag defended himself by saying that he had purchased the meteorite from a mineral dealer who claimed that the meteorite belonged to the landowner and sold it to Haag for $200,000. Eventually, however, El Chaco was returned to Campo del Cielo and Haag was released after posting bail and leaving Argentina. Now the meteorite is protected by law.

Surprisingly, it wasn't until 2016 that the largest known fragment was unearthed. The meteorite is named Gancedo after the nearby town of Gancedo, which provided the equipment for the excavation. Gancedo has a mass of 30,800 kilograms making it the largest known fragment of Campo del Cielo.

Meteorite impact, age and composition

At least 26 craters have been mapped that make up the Campo del Cielo crater field, the largest measuring 115 x 91 metres. The field covers an area of 3 x 18.5 kilometres and the associated fall zone, where smaller fragments of the meteorite were found, covers a further 60 kilometres. Many small fragments have been found in some of the large craters, which means that these pieces separated at a high altitude and only hit the ground after the larger piece impacted. The Native Americans must have watched a truly phenomenal and breathtaking "fireworks display". Not surprisingly, they associated the meteorites with the spectacle and called the site the "celestial field". The iron for the burial of the tools was truly a godsend for them.

In order to date the fall, samples of burnt wood were collected from beneath the meteorite fragments and analysed for carbon-14 composition. The results indicate a fall date of approximately 4,200-4,700 years ago. Or 2,200-2,700 years BC. The age is estimated at 4.5 billion years. So, like other meteorites, this one was formed during the very formation of our solar system and is a fantastic glimpse into a time when the world around us was just beginning to form.

The fragments contain an unusually high density of inclusions, at least for an iron meteorite; this may have contributed to the fact that this meteorite broke into more small fragments than is usual for iron meteorites. The average composition of the Campo del Cielo meteorites is 3.6 ppm iridium, 87 ppm gallium, 407 ppm germanium, 0.25% phosphorus, 0.43% cobalt and 6.67% nickel, with the remaining 92.6% being iron.